Exclusive Interview: A Look Inside DermaSensor’s Journey to Innovation with CEO, Cody Simmons

In this edition of our Experts in Motion series we interview Cody Simmons, CEO of DermaSensor, a leading provider of innovative solutions for skin cancer detection. Take a look as he recounts the 15-year journey to FDA approval and the challenges of bringing this breakthrough technology to the forefront of healthcare innovation. He shares personal insights and the profound impact DermaSensor could have in revolutionizing dermatological care by making skin cancer detection accessible to a wide range of healthcare providers. This story is not just about technological achievement; it’s about persistence, breakthroughs, and the potential to save lives by promptly spotting the deadliest of skin cancers.

FJP: Cody, thank you for joining us today. For those reading this who are unaware of DermaSensor, Could you share an introduction to you, DermaSensor, and the company’s mission and journey so far.?

Cody: That’s a big one, but I’ll try to keep it quick. I’ll start with where we are status-wise. We received our FDA clearance in January 2024, and for the first time in the United States, 1 million physicians can now provide their patients with automated quantitative skin cancer risk results, and they can do so with our device quickly and completely non-invasively. That’s a milestone I’m very happy to have finally achieved for the company. It’s been a 15-year road, and for me, with the company, eight years this month. It’s been quite a long and expensive journey, but I am beyond excited to be here today.

R&D to date has cost us about $25 million and we have conducted 13 clinical studies in total, with six submitted to the FDA. So quite a long road. But a long road is well worth taking because skin cancer is more common than all other cancers combined. However, it’s basically completely curable if caught early. Literature shows that 99% of melanoma cases, the deadliest ones, are curable if detected early. And unlike many cancer types, it’s literally visible. Visible on people’s skin, not just to dermatologists but to hundreds of thousands of frontline providers, like family medicine doctors, internal medicine, OB-GYNs, etc. If these providers were better equipped to assess those lesions, then we could really have a big impact on patient care. That’s really been our focus.

It’s been a really exciting start so far and pretty overwhelming, frankly. The amount of interest we’ve received, not just from individual physicians but also from large health systems, concierge physicians, etc., has been immense. It’s been an 8-year (or 15-year) overnight success.

FJP: Congratulations on the FDA approval. That was great to see, and I’m not surprised to see the level of interest that you guys have garnered. Early cancer detection really remains the holy grail if we are to make a big difference in patient outcomes in oncology. There’s been a lot of attempts but also a lot of failures, so seeing your approval is a MedTech success story, and a lot of people are rooting for you guys.

Cody: Thank you. It’s interesting; there’s been a buzz in this field for a long time. About 35 years ago, in 1990, the first paper came out on applying algorithms to images of skin lesions. Despite hundreds, potentially thousands, of researchers and dozens of companies that have tried to tackle this problem using various types of photos – dermoscopy, standard clinical photos, smartphone photos, et cetera – none of them have been able to make it through, and so none are available today using any form of imaging. There’s also not a single product available on the market for PCPs that provides any kind of automated skin cancer risk assessment or prioritization of different diagnoses or anything like that is FDA-cleared.

We took a bit of a different technical approach. Obviously, we don’t take photos. But we do use light. It’s a type of optical spectroscopy that, in the early days, we thought would win from a technical standpoint. When we licensed the tech from Boston University, it was a 30-pound microwave-sized device that we spent a lot of time and money miniaturizing. It felt very painful on the front end when a lot of companies were using off-the-shelf smartphones or little cameras. But I think all the hard work and just following good science and technology that can ultimately be quick and easy to use for the customers has paid off.

FJP: What were some of the issues the photo-based solutions ran into?

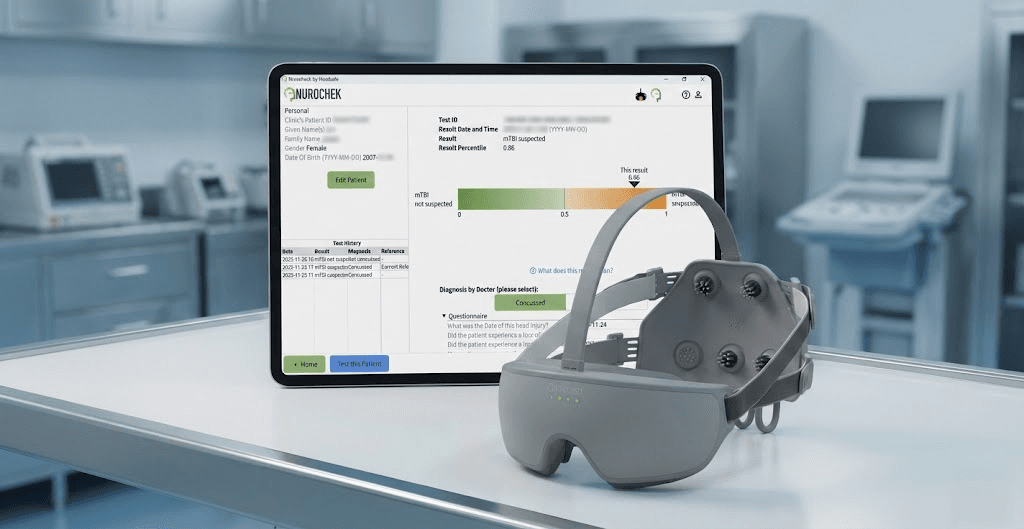

Cody: I think there are a lot of photo-based solutions, for example, in ophthalmology, like the automated fundus AI ones, where they have to reject something like 20% to 30% of patients because the photos are not good enough. In papers using photos of skin lesions, we often see numbers as high or higher than that. So that leads to something really exciting about our device. We give an answer every time. There are also no restrictions based on patient skin type since the technical papers on our technology and our validation studies suggest skin types do not impact device performance (although our studies had smaller sample sizes for darker skin types). This has led to a lot of excitement in the medical community from a health equity standpoint because we’re not visually assessing the skin. We’re assessing cellular-level features like nuclear size and the presence of condensed chromatin, the same kind of things that pathologists look at under a microscope. That’s what we’re assessing.

FJP: Our readers all know that getting FDA approval, commercializing, and making things happen in the MedTech space is very difficult. What would you say you guys have learned through the process? Can you give our readers a sense of what it actually takes? What have you learned in the past eight years?

For us, something that has been tremendously helpful is that there were a couple of similar devices that were approved for dermatologist use and just for melanoma. When I talk about the first automated device for skin cancer, or for all physicians, the key differentiator is the use for skin cancer generally. So melanoma, BCC, and SCC, and for physicians, I say physicians purposefully because the idea is to target all physicians who are not already experts, who are not dermatologists. That was really our focus because we saw the challenges that a couple of earlier products had with targeting the derm community, since they are already experts and doing biopsies is their standard management approach. Even knowing that it was hard not to do the same. I’ll admit it was. A lot of dermatology KOLs, advisors, investors, and even reimbursement people tried to dissuade us from targeting primary care. There were a lot of folks and winds pushing us toward dermatology.

Every person in the world, including Dermatologists, could get better at their job, but they’re already quite good at assessing skin. I mean, it’s their specialty by definition. On the other hand, there are hundreds of thousands of other doctors who have to make decisions nearly daily, if not daily, as to whether to refer a mole that a patient points at, for example. They can’t abstain from answering; they have to decide whether to refer or not, even though they aren’t specialists in making those assessments. From a population health standpoint, this wasn’t a new insight. The Dermatology community has been trying to get PCPs to be more hands-on and effective at assessing skin cancer for many years. They have been training to get PCPs to use Dermatoscopes for decades, but the subjective nature and high training time needed have resulted in little use of them in primary care.

I’m really glad we held our ground and focused on the primary care market. I think the large amount of excitement and interest from the medical community and from customers has shown this is the right route to go, and hopefully, that stays the case. You have to make sure to learn from the relevant devices ahead of you.

In retrospect, I would have tried to do even more learning from relevant devices. We certainly spoke with some physicians who were involved in those early dermatology and Melanoma devices. But in retrospect, I think we should have gotten even closer. Maybe even hired some of the same statisticians or consultants that worked on those products and really picked their brains as to what they did do, why, and how it was wrong, and how we can avoid some of the same mistakes since neither of those devices gained any meaningful commercial traction.

FJP: What are some other ways you are differentiated versus some of those early devices?

Cody: Obviously, the price point is lower, but I think it comes down to really having that product market fit and a device that’s highly usable. At the end of the day, we followed the customer and that’s where the market’s going to be, at least so far. Early on, we had some advisors telling us not to make the device small and easy to use because it would make the product low-cost and we wouldn’t get sufficient reimbursement, but we didn’t care about trying to add unnecessary costs to the often-dysfunctional payer reimbursement system.

We were focused on building a product with great unit economics, no expensive disposables, and that was going to be really quick and easy to use. A product that hundreds of thousands of doctors will actually have an interest in using, and it’s not going to be a pain to do so. If it’s so low-cost, easy to use, and such an impactful product, the payment stuff will work itself out. That wasn’t always the most popular approach with investors, as you can imagine. Time will tell whether that was the right call, but there are other products on the market that took the, I’d say, more traditional approach and really struggled.

FJP: Certainly, your approach is a breath of fresh air. When we think about some of the big issues in health care, we’re talking about labor shortages, we’re talking about access and equity, we’re talking about solutions that fix actual problems and not just add cost and complexity, and I think that you guys have an approach that can do that. I’d love to hear your thoughts on that.

Cody: A lot of it, at the end of the day, is sort of luck in timing; I think if we’d been a few years earlier, we might have gone after the same kind of dermatologist approach because of those pressures or dynamics I explained earlier but also because there hadn’t been AI primary care disease detection tools yet. But then we’ve seen successes in PCP detection tools and actually brought on board Jason Bellet, the co-founder of Eko Health, as a commercial advisor. Eko’s digital stethoscope is now in use by hundreds of thousands of frontline providers in the US. Handheld ultrasounds, which were the hot new medical devices a few years ago now, are another great example, and it seems like there are a half dozen similar products out there at this point. Some of those products have paved the way for a commercial model of direct sales to large health systems and investing in digital marketing and medical affairs to have that bottom-up awareness so you can really have some significant success.

FJP: What have been some of your biggest challenges and surprises? I’ve heard you mention in other interviews that you guys did way more studies than you expected, for example. vantages?

Cody: Product development was definitely a big one. My background is in bioengineering; I was in a biomaterial lab at Stanford for my master’s work. I’m not a hardware electronics guy, but I knew enough to listen and follow a bit of what the real engineers were saying. The hope when I came on board was to quickly miniaturize this 30-pound device, but we realized that this was not going to be a one-year project. I’ll admit though, we did not think it’d be a three-and-a-half-year project as it ended up being.

If we had known it would take that long, I don’t know if we ever would have done it. I don’t know if the investors or even I would have signed up for three years just to develop the device that we then needed to do additional multiyear studies on. It would have been a very formidable ask when you think of investment, ROI, and all that stuff. It also put the company in a tough spot because we started off with a one-year timeline, and then you’re just constantly behind on time and over budget.

And so then the problem self-perpetuates because while you may want to work with this new vendor that has great engineers in Boston or XYZ location, you don’t have money for it. You are then forced to work with the lowest cost option and just hope that works out, and of course that then often is less effective and takes longer.

I’ve learned and shared with people that whenever you have a major setback – whether study-related, study timeline change or product setback and timeline change, just reevaluate your whole approach and strategy because even with your well-laid plans, when one of the pieces of the plan changes, you realize other doors could open. I think I could have done a better job at that in retrospect, but I think I did a decent job. We ended up sneaking in two or three more clinical studies than we planned due to product development and manufacturing delays, due to COVID, and due to our pivotal study taking twice as long as we thought it would. And it really helped on the validation side of things.

I think whenever new meaningful information comes to light about your products, about your development plans, or about your growth plans, you should consider not just how the change impacts this one element but also how it impacts all aspects of the plan. I think it’s an issue if you’re not doing that kind of holistic, company-wide development plan reevaluation at least a couple times a year, but probably a few times a year because in those early stages, you’re facing setbacks a fair amount.

Nothing works out quite the way you envisioned. Your own timelines and projections, you have to take those with a big grain of salt because you might get there, but you won’t get there the way you think you’re going to get there.

FJP: How are you guys working to ensure adoption? It seems like you guys have incorporated the voice of the customer early but are also doing some pretty interesting things to drive visibility.

Cody: It’s definitely been helpful having team members who have been through product launches many times. Our senior director of marketing, Jacqueline, was at Abbott and a couple of other relevant companies for many years, and obviously, the point-of-care diagnostics tools were used. Our chief commercial officer, Larry, has launched products and taken two startups from brand new product launch introduction through to exit two or three years later. At my last startup, I was the BD lead for launching two new medical devices. I think having people who have been there and gone through it before is definitely helpful. A lot of different ideas and insights. If you’re a first-time founder or first-time leader in launching a new product, you need at least consultants, but preferably full-time team members, people who have been through a similar stage and process at least once or twice.

We also did a lot of market research leading up to clearance, really understanding pricing and kind of what market segments are the best fit. Another thing that we did, which I think some people may not have the luxury of doing given regulatory considerations, was a lot of pilot efforts abroad, a bit in Germany and a decent amount in Australia.

In Australia, we received a solid number of real-world insights and feedback and actually made a pretty big product change as a result. We used to just have a binary output – higher risk or lower risk. We changed the terminology because a lot of people got freaked out by the higher-risk terminology. So we switched to the terms “investigate further” and “monitor”. That was an important terminology change that we got advisors’ input on, and we did surveys with doctors to see what they preferred. But the big change was switching to a scale because we’re not explainable AI, and while the higher risk or lower risk output in the pilots was simple, physicians kept asking how high the risk for positive results was. Does the device think the given lesion just barely passes the positive risk threshold, or is it very high risk? They wanted a little more meat in the output. We ended up adding one to ten scales for the positive result. So negative is just monitor, no more detail provided than that, but in the investigation further cases, the positive result comes with this one to ten scale that indicates the algorithm’s confidence level, or the level of similarity to malignant lesions. What’s really powerful about that? In the pivotal study with over 1,000 patients and 22 study centers led by Mayo Clinic, the likelihood of a positive result was cancerous, ranging from 6% to 61%, for scores from one to ten accordingly.

If the result is 6%, that’s not nothing, right? It could still be worth seeing a dermatologist, especially if it’s concerning for melanoma. But those higher scores, I mean, once you’re getting to a coin flip of having cancer, that’s really valuable for doctors to know, and it may then lead to an urgent referral that they can mark in their EMR, or they can call a dermatologist to get a patient in urgently. The majority of health systems we’ve spoken with so far have wait times of more than six months for dermatology appointments, so they’re definitely excited about using the tool to prioritize patients who have a high risk of cancer.

If you’d like more expert interviews like this one with Cody Simmons, subscribe to our newsletter here and check out our other Expert in Motion interviews here.